Welcome to the Marriage Recovery Research Project.

The Marriage Recovery Research Project is based in part on the Favors Life Recovery Series Curriculum and Overcoming Setback Series Curriculum.

This research project is new and in development. Sample series topics will always include the Big Five personality traits, goal orientation, mindset, parenting styles, mate value, and mate switching.

However, the research will focus primarily on John Bowlby’s concepts of secure base, attachment theory, and maternal deprivation theory as well as concepts related to psychopathology, psychoanalysis, and cognitive behavior theory. The list is not exhaustive.

A unique aspect of the Marriage Recovery Research Project will center on marriage and attachment, marital indifference, marriage as a secure base, and marriage as a refuge. Researching why romantic partners cheat is just as important as studying why they cheat consistently and return home to their marital partners and to the marriage by extension.

The Marriage Recovery Research Project will develop tentative research questions, an annotated bibliography, and the outlines of potential journal articles.

It is not clear if audio lectures that apply psychology concepts to the project will be necessary, but such audio lectures might be central for processing the information when considering moving from marriage setback to marriage recovery.

This project would be ideal for marital and long-term partners struggling with a romantic partner who continues to cheat despite warnings and has moved into a state of infidelity. A partner who has cheated once and who has no longer cheated within the marital and/or long-term romantic relationship would not be a primary subject of study.

Instead, the partner who says, “I want to come home,” but still decides to step out of the marital bed and cheat repeatedly would be a primary subject of study. It is suggested that the latter partner may have attachment issues that prevent him or her from sticking to the marital vows. The unmarried long-term romantic partner would be considered because there is an implicit vow to stay and remain committed to the relationship.

The development of content is tentative and subject to change.

Last revision 10/7/2021, 1/23/2023, 4/17/2023, 12/17/2023, 2/1/2024, 8/3/2024

New Title

Marital Setback: Why Romantic Partners Live as Roommates, Tips for Rebuilding Hope, A Biblical Intervention is an urge to marital partners currently living together as roommates to address areas of misalignment between God and the marriage and between themselves and the marriage.

Marriage should not be a convenience factor or rebound target when life is not supporting one’s individual dreams. Just because one area of life does not work out does not equally mean that marriage is irreparable.

Click the “Rebounding” tab for access to research.

New Companion

Overcoming Counterfeit Setback is a new companion to the Marriage Recovery Research tab and later for the Overcoming Marital Setback Workbook (in progress).

This new series deals with considerations leading up to marriage and the consequences of choosing the wrong person. It explores why men choose “potential” who masquerades as a “counterfeit” over whom God desires for them and marriage.

Click the “Overcoming Counterfeit Setback” tab to access videos. A companion title might be in progress.

Mission Statement

The mission of the Marriage Recovery Research Project is to initiate a study of marital infidelity, create research questions, design a survey/measure, and develop an annotated bibliography. The project may or may not proceed after initial research.

Tentative Description

The Marriage Recovery Research Project is formed to study the following phrase: marriage as a secure base.

For the better part of three years “marriage as a secure base” has been a subject of interest and tentative outlining followed. However, there has been no consistent undertaking to study the phrase and/or consider how to approach the subject matter.

However, the word “refuge” surfaced as a possible term for understanding why marriage would be a secure base for a romantic partner who consistently cheats, committing infidelity, but returns to the marital home, the marital bed, and to the marriage proper.

Understanding that marriage might be the equivalent to a refuge for some marital partners brought the phrase “marriage as a secure base” to the forefront, which resulted in conducting preliminary research based on keyword searches.

Thus, “Marriage as a Secure Base for Infidelity, Distinguished from Cheating” became an ideal focus of study considering that there could be a possible answer to why romantic partners cheat and their consistent justification for doing so.

Secure Base Defined

John Bowlby connects “secure base” to attachment theory. Bowlby defines the term as a relationship with a sensitive and attachment figure, who may be a parent or a caregiver. For example, a child may feel secure with his or her “secure base” because the parent or caregiver meets the child’s needs and the child believes the parent or caregiver to be a safe haven particularly when feeling distressed. Attachment can be either secure or insecure, resulting in different reactions from a child whose needs are met or not met.

Development of this section is forthcoming. Last revision 3/10/2022.

Tentative Hypothesis

Marital and long-term, cohabitating partners use marriage as a secure base to commit infidelity because marriage represents a refuge, a stable location upon which cheating partners can return. The affair partner is not a refuge. Men, or people in general, reject marital stability for emancipation in marital instability (new thesis, 8/3/2024).

Research Question(s)

The following research question(s) may help to guide this project. Here is a tentative research question:

Why does a marital or long-term romantic partner continue to cheat in a marriage or long-term romantic relationship, despite warnings?

It is assumed that marital or long-term romantic partners may cheat for numerous reasons, but connecting attachment to infidelity might be a useful strategy. However, this strategy might be considered repetitive.

Conducting the annotated bibliography will determine if this research might be redundant.

Preliminary Thinking

The following questioning, outlining, and categorizing are considered in this research process. Definitions are wholly adapted.

Infidelity

Infidelity is defined as the action or state of being unfaithful to a spouse or other sexual partner. It is also defined as unbelief in a particular religion, especially Christianity.

- But the cheating person chooses marriage even though he or she doesn’t believe in marriage?

- If the cheating partner is not dissatisfied with the relationship, then cheating may be useful for what reason?

Cheat

To cheat means to act dishonestly or unfairly in order to gain an advantage, especially in a game or examination. The term also means to avoid something undesirable by luck or skill.

Synonyms for “cheat” include avoid, escape, evade, elude, steer clear of, dodge, and duck.

They’re not steering clear of marriage because they return to it after their cheating incidents.

- Therefore, “what” are they steering clear of?

- What is the cheating part of the relationship?

- What and why are they cheating?

To cheat means to desire exit. They don’t want to exit the marriage, per se.

- What do they want to exit?

- They want to exit the attachment?

Cheaters want the theory of marriage, but they do not want the practice of marriage.

Five Questions for Good Research

The following questions derive from an Internet search of the concept of developing research questions:

- What is the problem to be solved?

- Who cares about this problem and why?

- What have others done?

- What is your solution to the problem?

- How can you demonstrate that your solution is a good one?

These questions will be answered at a later date. However, one or more solutions to the problem might consider the reasons why a person cheats consistently because that person has attachment issues. If this is true, then cognitive behavior therapy might be a solution.

Tentative Survey Questions

The following tentative survey questions serve as a guide for how to conduct human subjects research, which will require approval through a participating institution.

- Are you married or cohabitating with a long-term romantic partner?

- How long have you been married or cohabitating with a long-term romantic partner?

- Have you cheated in your marriage or in your long-term romantic partnership?

- Does your romantic partner know you have cheated in your marriage or long-term romantic partnership?

- What did your spouse or long-term romantic partner do after this knowledge?

- Did you or your partner return to the marriage or long-term romantic partnership?

- Did you cheat again after you and your marital or long-term romantic partner return to the relationship?

- Age

- Demographics

- Comment

It is clear that the survey questions are too wordy and need revising, but they serve as a possible guide for how to form better survey questions.

The survey may need to be structured as a Likert scale. For example, the following question might be useful for supporting this strategy:

- How likely are you to cheat on your partner again?

The Likert scale is more useful for scaling responses in survey research.

Current Progress as of 8/3/2024

The current research progress includes defining the argument that marriage is a secure base and extending it to the idea of conflicting forces between stability and instability. This is what I’m considering in italics.

Men want stability, but they create instability. This goes back to my working thesis that marriage is a secure base for romantic rebounding. Men use marriage to create instability. Why? They don’t want marriage. They don’t want the responsibility and accountability that comes with marriage. But they want the convenience that marriage brings. They suffer from insecure attachment, and they want to attach securely to a base, to a host. Men are aliens to marriage, seeking a host.

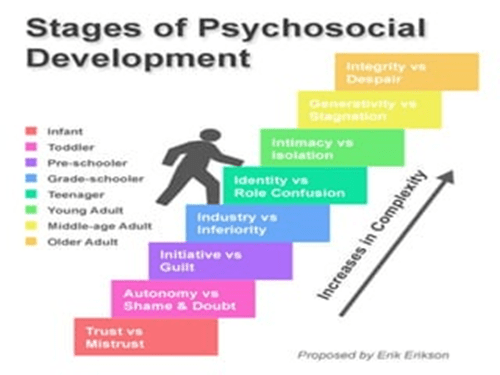

These are ideas I journaled today. In addition, I have been researching psychology theories for another research project, particularly Erik Erikson’s (1902-1994) Stages of Psychosocial Development, which are based on Freud’s psychosexual theory.

According to Erikson, we experience eight (8) stages of development throughout the lifespan; successful completion of each stage results in a sense of competency and healthy personality. We are essentially motivated by a need to achieve competence and mastery, but each stage includes a crisis that we must resolve before moving to the next stages. Here is a quick visual. The credit is included in the visual.

The stages are briefly explored below followed by a tentative bibliography of Erikson’s work. The information is summarized from an online document titled “Erikson’s 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development.” Click the link for a brief view of the topic. Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development is also part of the general psychology textbook.

Based on new research, a connected tentative research thesis: Men, or people in general, reject marital stability for emancipation in marital instability.

Trust vs. Mistrust

Infants from birth to 12 months need to feel safe and learn that adults can be trusted. Infants need predictability. Thus, responsive parenting creates trust in an infant. Non-responsive parenting creates mistrust in an infant. This means that infants feel securely attached to a parent or caregiver responsive to its needs while infants feel insecurely attached to a parent or caregiver unresponsive to its needs.

Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt

Toddlers aged one-year old to three years old explore the immediate world around them guided by a responsive or unresponsive parent. Their goal is to resolve issues with autonomy while exhibiting a “me do it” strategy. When a parent or caregiver permits a toddler to choose for himself or herself, the toddler experiences a sense of independence. When the toddler is not permitted this sense of independence, it leads to low self-esteem, or shame/doubt.

Initiative vs. Guilt

Children at preschool ages, from three years old to six years old, can initiate and assert control over activities in their immediate world. They become social creatures through play and interactions with other children. They learn, plan, and achieve goals through interaction and mastering tasks. Taking initiative gives them a sense of responsibility and helps them to develop self-confidence and a sense of purpose. However, over-controlling parents may produce feelings of guilt in children who cannot pursue and achieve a sense of ambition.

Industry vs. Inferiority

Elementary school age children from six years old to 12 years old often compare themselves to their peers. Their goal is to assess their own competence against the competence of their peers. Which one measures up? is a guiding question that often leads to pursuit of industry as they accomplish tasks or leads to a sense of inferiority if they feel inadequate. An inferiority complex might develop during this time in adolescence leading to adulthood.

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Adolescents aged between 12 years old and 18 years old confront the issue of problem-solving when it comes to sense of self. They must resolve questions, such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Adolescents who exhibit a firm belief system have a strong sense of identity. They remain true to their beliefs in the face of personal crisis.

However, adolescents who struggle with who they are in search of an identity develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. These are adolescents who are often pressured by their parents to become what they believe for the adolescent. They struggle to “find themselves” when they reach adulthood.

Intimacy vs. Isolation

In early adulthood between a person’s 20s to early 40s, people should have developed a sense of self during the adolescence period that prompts them to pursue intimacy with others, i.e., share their lives with others. When conflicts in previous stages have not been resolved, adults may have trouble developing connections with others and maintaining successful relationships. If adults have a strong sense of self, they will be successful in pursuing intimate relationships. If they struggle with the self and their self-concept, they may pursue emotional isolation, feeling loneliness in their adulthood.

Generativity vs. Stagnation

Middle adulthood begins in a person’s 40s and lasts to the 60s. Middle adulthood is a period where individuals contribute to the development of others, i.e., preparing the next generation. It is during this period of middle adulthood that persons discover their life’s purpose and contribute through volunteer work and mentorship. The goal is to contribute meaningful work to the advancement of society.

When individuals are productive in their pursuits, they exhibit generativity. However, if they are selfish and unwilling to contribute to the betterment of others, they reflect stagnation. There is little interest in self-improvement and productivity.

Integrity vs. Despair

The mid-60s is defined as persons slowing down and moving into retirement. This is considered late adulthood when people reflect on their lives to determine the significance of their accomplishments. They either feel a sense of satisfaction and proud of their accomplishments, which reveals their integrity, or they feel regret for the choices they made, which reveals their despair.

People who do not feel like they have been successful with their lives believe they have wasted their lives; they often use language, such as “would have,” “should have,” and “what could have been.” Feelings of despair is rooted in bitterness with life.

This is an overview of Erikson’s 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development. A brief bibliography is housed in the next section. The goal is to pair the terms “psychosocial development” with “marriage” or “marital infidelity” or any other association to focus research efforts. Terms might also include “attachment” as a search task.

Keyword Search Results

The following sources are based on a preliminary keyword search to begin categorizing references and hopefully categorizing the research:

Marital Indifference

Abbasi, I.S., & Alghamdi, N. G. (2016). Polarized couples in therapy: Recognizing indifference as the opposite of love. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 43(1). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304582707_Polarized_Couples_in_Therapy_Recognizing_Indifference_as_the_Opposite_of_Love

Alternate Link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1113596?journalCode=usmt20

Canel, A. N. (2013). The development of the marital satisfaction scale (MSS). Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 13(1), 97-117. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016640.pdf

Futris, T. G., & Adler-Baeder, F. (2013). The National Extension Relationship

and Marriage Education Model: Core teaching concepts for relationship and marriage enrichment programming. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Available from http://www.nermen.org/NERMEM.ph

Hsieh, N., & Hawkley, L. (2020). Loneliness in the older adult marriage: Associations with dyadic aversion, indifference, ambivalence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(10), 1319-1339. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7041908/

Hymowitz, K., Carroll, J. S., Wilcox, B., & Kaye, K. (2013). Knot yet: The benefits and costs of delayed marriage in america. The National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Retrieved from http://nationalmarriageproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/KnotYet-FinalForWeb.pdf

Irving, R. W. (1994). Stable marriage and indifference. Discrete Applied Mathematics, 48, 261-272. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0166218X9200179P

Kachadourian, L. K., Fincham, F., & Davila, J. (2005). Attitudinal ambivalence, rumination, and forgiveness of partner transgressions in marriage. Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 31(3), 334-342. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/Kachadourian-Role_of_Ambivalence_and_Rumination_on_Forgiveness.pdf

Liu, Y., & Upenieks, L. (2020). Marital quality and well-being among older adults: A typology of supportive, aversive, indifferent, and ambivalent marriages. Research on Aging, 43(9-10). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344903632_Marital_Quality_and_Well-Being_Among_Older_Adults_A_Typology_of_Supportive_Aversive_Indifferent_and_Ambivalent_Marriages

Sage Pub Link: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0164027520969149

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4), 139-158. Retrieved from https://www.amherst.edu/system/files/media/1668/Lundberg.PDF

Luo, S., & Klohnen, E. C. (2005). Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: A couple-centered approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 304-326. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp-882304.pdf

Pecker, G. S., Landes, E. M., & Michael, R. T. (1977). An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1141-1187. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1837421

Scott, E. S. (2000). Social norms and the legal regulation of marriage. Columbia Law School. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1483&context=faculty_scholarship

Sharaievska, I. (2012). Family and marital satisfaction and the use of social network technologies. Dissertation. University of Illinois-Champaign. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/10208516.pdf

Stritof, S. (2020). Saving your relationship when your marriage hurts. VeryWellMind.com. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/when-your-marriage-hurts-2303618

Vernick, L. (n.d.). Is marital indifference emotionally abusive? LeslieVernick.com. Retrieved from https://www.leslievernick.com/pdfs/Is%20Marital%20Indifference%20Emotionally%20Abusive.pdf

Weiss, Y. (1997). The formation and dissolution of families: Why marry? Who marries who? And what happens upon divorce? Handbook of Population and Family Economics. Retrieved from http://public.econ.duke.edu/~vjh3/e195S/readings/Weiss.pdf

Related Search Results

Research the following at a later date: theories of marital conflict, effects of marital conflict, factors that lead to marital instability

Factors That Lead to Marital Stability/Instability

Heaton, T. B. (2002). Factors contributing to increasing stability in the united states. Journal of Family Issues. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0192513X02023003004?journalCode=jfia

Lehrer, E. L., & Son, Y. J. (2017). Marital instability in the united states: Trends, driving forces, and implications for children. Retrieved from https://ftp.iza.org/dp10503.pdf

Maciver, J. E., & Dimkpa, D. I. (2012). Factors influencing marital stability. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1). Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/regin/AppData/Local/Temp/10977-Article%20Text-41811-1-10-20200419.pdf

Alternative Link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266287268_Factors_Influencing_Marital_Stability

Mueller, C. W., & Pope, H. (1977). Marital instability: A study of its transmission between generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 39(1). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/351064

Marriage and Attachment

Hollist, C. S., & Miller, R. B. (2005). Perceptions of attachment style and marital quality in midlife marriage. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=famconfacpub

MacLean, A. P. (2001). Attachment in marriage: Predicting marital satisfaction from partner matching using a three-group typology of adult attachment style. Thesis. Purdue University. Retrieved from https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3043755/

Alternative Link: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304724794

Alternative Link: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3043755/

Marcus, L. (1997). The relationship of adult attachment style, communication, and relationship satisfaction. ETD Collection for Fordham University. AAI9730100. Retrieved from https://research.library.fordham.edu/dissertations/AAI9730100/

Research Results for Erikson

These are the search results for Erikson’s 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development, using the following key terms search (bolded sub-headings). The search is preliminary. Additional research will result by reviewing the bibliographies of the source materials.

Using the following visual as a guide, the goal is to conduct research that explores marital stability or marital instability (conflicting crises) from least complex to most complex. The research will be about stability or lack thereof within the marital structure.

Keyword Search: “Marriage & Psychosocial Development“

Adigeb, A. P., & Mbua, A. P. (2015). The influence of psychosocial factors on marital satisfaction among public servants in cross river state. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: G Linguistics & Education, 15(8). Retrieved from https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume15/2-The-Influence-of-Psychosocial-Factors.pdf.

Bell, L. G., & Harsin, A. (2018). A prospective longitudinal of marriage from midlife to later life. Couple Family Psychology, 7(1). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.indianapolis.iu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/73d5f5ec-cbce-4b67-a02a-2ee83b0f78df/content.

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62. Retrieved from https://www.fincham.info/papers/decade%20review.pdf.

Bradbury, T. N. (n.d.). The developmental course of marital dysfunction. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://peplau.psych.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/141/2017/07/Hill-Peplau-98.pdf.

Canel, A. N. (2013). The development of the marital satisfaction scale (MSS). Educational Science: Theory & Practice, 13(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016640.pdf.

Cook, J. L., & Jones, R. M. (2002). Congruency of identity style in married couples. Journal of Family Issues, 23(8). Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=68e3fe2f354fc97dd12bb0ecb20daa9186871b4e.

Dern, T. S. (2002). Effect of employment on generativity in married mothers. The Scholars Repository. Loma Linda University. Retrieved from https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1714&context=etd.

Dush, C. M. K., Taylor, M.G., & Kroeger, R. A. (2008). Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relationships, 57(2). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3650717/.

Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2002). Forgiveness in marriage: Implications for psychological aggression and constructive communication. Personal Relationships, 9. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/Fincham-Forgiveness_on_Aggression_and_Communication_in_marriage.pdf.

Goel, S., Khandelwal, S., Evangelin, B., Belho, K., & Agnihotri, B. K. (2022). Psychological

effects of early marriage: A study of adolescents. International Journal of Health

Sciences, 6(S2), 6714–6727. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS2.6628. Link: file:///C:/Users/regin/Downloads/IJHS-6628+6714-6727.pdf.

Hamilton, V. E. (2012). The age of marital capacity: Reconsidering civil recognition of adolescent marriage. Boston University Law Review, 92. Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/law/journals-archive/bulr/volume92n4/documents/HAMILTON.pdf.

Hsu, T., & Barrett, A. E. (2020). The association between marital status and psychological well-being: Variation across negative and positive dimensions. Journal of Family Issues. Retrieved from https://midus.wisc.edu/findings/pdfs/2084.pdf.

Montgomery, M. J., Hernandez, L., & Ferrer-Wreder, L. (2008). Identity development and intervention studies: The right time for a marriage? Faculty Publications-Graduate School of Counseling. George Gox University. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/gsc/article/1041/&path_info=Marilyn_Montgomery___Identity_Development_and_Intervention_Studies__The_Right_Time_for_a_Marriage_.pdf.

Online Learning Center. (2024). Psychosocial development in adulthood. Human Development, Tenth Edition. Retrieved from https://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0073133809/student_view0/chapter14/.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1). Retrieved from https://www.healthymarriageinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-Longitudinal-Course-of.pdf.

Lang, D., Cone, N., Lally, M., Valentine-French, S., Mather, R., & Loalada, S. (2022). Relationships in middle adulthood. Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-Being. Iowa State University Digital Press. Retrieved from https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/individualfamilydevelopment/chapter/relationships-in-middle-adulthood/.

Muhammad, D. T. A. (2023). Psychological stress and its relation to marital compatibility among early married couples. Journal of Sustainable Development in Social and Environmental Sciences, 2(1). Retrieved from https://jsdses.journals.ekb.eg/article_279259_4a0d6f55147c56cf19f397a733c1895d.pdf.

Oh, J. E. (2013). Psychosocial development in south korean couples and its effects on marital relationships. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 24(3). Retrieved fromhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/08975353.2013.817264. (Note: This source must be purchased.)

Rockwell, R. C., Elder, Jr., G. H., & Ross, D. J. (1979). Psychological patterns in marital timing and divorce. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42(4). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3033810. (Note: This source must be purchased.)

Sandu, M., & Salceanu, C. (2020). Psychosocial factors that influence marital couple duration. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 5(151-160). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344715084_Psychosocial_factors_that_influence_marital_couple_duration.

Weinberger, M. I., Hofstein, Y., & Whitbourne, S. K. (2008). Intimacy in young adulthood as a predictor of divorce in midlife. Personal Relationships, 15(4). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2733523/.

Wilson, A. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2005). How does marriage affect physical and psychological health? A survey of the longitudinal evidence. Retrieved from https://docs.iza.org/dp1619.pdf.

Note: There are more research and scholarly works under this search term. I will research and save documents later. This bibliography list is a good start.

How to Get Paper Published

Fried, P. W., & Wechsler, A. S. (2001). How to get your paper published. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 121(4), 53-57. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022522301133118

Copyright (C) 2018-2024 Regina Y. Favors. All Rights Reserved.

Feedback

We appreciate your feedback.